Complexity, Energy and Money

Using behavioral and complexity theory tools in tandem provides great insight into how the currency wars will evolve if money printing and debt expansion are not arrested soon. The course of the currency war will consist of a series of victories for the dollar followed by a decisive dollar defeat. The victories, at least as the Fed defines them, will arise as monetary ease creates inflation that forces other countries to revalue their currencies. The result will be a greatly depreciated dollar—exactly what the Fed wants. The dollar’s defeat will occur through a global political consensus to replace the dollar as the reserve currency and a private consensus to abandon it altogether.

When the dollar collapse comes, it will happen two ways—gradually and then suddenly. That formula, famously used by Hemingway to describe how one goes bankrupt, is an apt description of critical state dynamics in complex systems. The gradual part is a snowflake disturbing a small patch of snow, while the sudden part is the avalanche. The snowflake is random yet the avalanche is inevitable. Both ideas are easy to grasp. What is difficult to grasp is the critical state of the system in which the random event occurs.

In the case of currency wars, the system is the international monetary system based principally on the dollar. Every other market—stocks, bonds and derivatives—is based on this system because it provides the dollar values of the assets themselves. So when the dollar finally collapses, all financial activity will collapse with it.

Faith in the dollar among foreign investors may remain strong as long as U.S. citizens themselves maintain that faith. However, a loss of confidence in the dollar among U.S. citizens spells a loss of confidence globally. A simple model will illustrate how a small loss of faith in the dollar, for any reason, can lead to a complete collapse in confidence.

Start with the population of the United States as the system. For convenience, the population is set at 311,001,000 people, very close to the actual value. The population is divided based on individual critical thresholds, called a T value in this model. The critical threshold T of an individual in the system represents the number of other people who must lose confidence in the dollar before that individual also losses confidence. The value T is a measure of whether individuals react at the first potential sign of change or wait until a process is far advanced before responding. It is an individual tipping point; however, different actors will have different tipping points. It is like asking how many people must run from a crowded theater before the next person decides to run. Some people will run out at the first sign of trouble. Others will sit nervously but not move until most of the audience has already begun to run. Someone else will be the last one out of the theater. There can be as many critical thresholds as there are actors in the system.

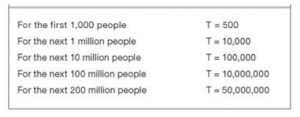

The T values are grouped into five broad bands to show the potential influence of one group on the other. In the first case, shown in Table 1 below, the bands are divided from the lowest critical thresholds to the highest as follows:

Table 1: HYPOTHETICAL CRITICAL THRESHOLDS (T) FOR DOLLAR REPUDIATION IN U.S. POPULATION

The test case begins by asking what would happen if one hundred people suddenly repudiated the dollar. Repudiation means an individual rejects the dollar’s traditional functions as a medium of exchange, store of value and reliable way to set prices and perform other counting functions. These one hundred people would not willingly hold dollars and would consistently convert any dollars they obtained into hard assets such as precious metals, land, buildings and art. They would not rely on their ability to reconvert these hard assets into dollars in the future and would look only to the intrinsic value of the assets. They would avoid paper assets denominated in dollars, such as stocks, bonds and bank accounts.

The result in this test case of repudiation by a hundred people is that nothing would happen. This is because the lowest critical threshold shared by any group of individuals in the system is represented by T = 500. This means that it takes repudiation by five hundred people or more to cause this first group to also repudiate the dollar. Since only one hundred people have repudiated the dollar in our hypothetical case, the critical threshold of T = 500 for the most sensitive group has not been reached and the group as a whole is unaffected by the behavior of the one hundred. Since all of the remaining T values are higher than T = 500, the behavior of those groups is also unaffected. None of the critical thresholds has been triggered. This is an example of a random event dying out in the system. Something happened initially, yet nothing else happened as a result. If the largest group that would initially repudiate the dollar is fixed at one hundred, this system is said to be subcritical, meaning it is not vulnerable to a chain reaction of dollar repudiation.

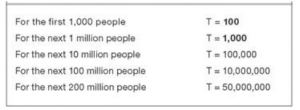

Consider a second hypothetical case, shown in Table 2 below. The groupings of individuals by size of group are identical to Table 1. This system of critical thresholds is identical to the system in Table 1 with two small differences. The critical threshold for the first group has been changed from T = 500 people to T = 100 people. The critical threshold for the second group has been changed from T = 10,000 people to T = 1,000 people, while all the other values of T for the remaining three groups are unchanged. Put differently, we have changed the preferences of 0.3 percent of the population and left the preferences of 99.7 percent of the population unchanged. Here is the new table of thresholds with the two small changes shown in bold:

Table 2: HYPOTHETICAL CRITICAL THRESHOLDS (T) FOR DOLLAR REPUDIATION IN U.S. POPULATION

Now what happens when the same one hundred citizens repudiate the dollar as in the first case? In this second case, one hundred rejections will trigger the critical threshold for one thousand people who now also reject the dollar. Metaphorically, more people are running from the movie theater. This new rejection by a thousand people now triggers the critical threshold for the next one million people, and they too repudiate the dollar. Now that one million have repudiated the dollar, the next threshold of one hundred thousand is easily surpassed, and an additional ten million people repudiate the dollar. At this point, the collapse is unstoppable. With ten million people repudiating the dollar, another one hundred million join in, and soon thereafter the remaining two hundred million repudiate at once—the rejection of the dollar by the entire U.S. population is complete. The dollar has collapsed both internally and internationally as a monetary unit. This second system is said to be supercritical, and has collapsed catastrophically.

A number of important caveats apply. These thresholds are hypothetical; the actual values of T are unknown and possibly unknowable. The T values were broken into five bands for convenience. In the real world, there would be millions of separate critical thresholds, so the reality is immensely more complex than shown here. The process of collapse might not be immediate from threshold to threshold but might play out over time as information spreads slowly and reaction times vary.

None of these caveats, however, detracts from the main point, which is that minutely small changes in initial conditions can lead to catastrophically different results. In the first case there was no reaction to the initial repudiation by a hundred people, while in the second example the entire system collapsed. Yet the catalyst was the same, as were the preferences of 99.7 percent of the people. Small changes in the preferences of just 0.3 percent of the population were enough to change the outcome from nonevent to complete collapse. The system went from subcritical to supercritical based on almost zero systemic change.

This is a sobering thought for central bankers and proponents of deficits. Policy makers often work from models that assume policies can continue in a steplike manner without unpredictable nonlinear breakdowns. Money printing and inflation are considered to be the answer to the lack of aggregate demand. Deficits are considered to be an acceptable policy tool to increase aggregate demand by stimulus spending in the public sector. Printing money and deficit spending continue from year to year as if the system is always subcritical and more of the same will have no extreme impact. The model shows this is not necessarily true. A phase transition from stability to collapse can begin in imperceptible ways based on tiny changes in individual preferences impossible to detect in real time. These weaknesses are not discovered until the system actually collapses. But then it is too late.

With this example of how complex systems operate and how vulnerable the dollar may be to a loss of confidence, we can now look to the front lines of the currency war to see how these theoretical constructs might manifest in the real world.

The history of Currency Wars I and II shows that currency wars are last- ditch responses to much larger macroeconomic problems. Over the past one hundred years, those problems have involved excessive and unpayable debts. Today, for the third time in a century, the debt overhang is choking growth and inciting currency war, and the problem is global. Europe’s sovereign borrowers and banks are in worse shape than those in America. Housing booms in Ireland, Spain and elsewhere were as reckless as the boom in the United States. Even China, which has enjoyed relatively strong growth and large trade surpluses in recent years, has an overleveraged shadow banking system run by provincial authorities, a massively expanding money supply and a housing bubble that could burst at any moment.

The post-2010 world may be different in many ways from the 1920s and the 1970s, but the massive overhang of unpayable, unsustainable debt is producing the same dynamic of deleveraging and deflation by the private sector offset by efforts at inflation and devaluation by governments. The fact that these policies of inflation and devaluation have led to economic debacles in the past does not stop them from being tried again.

What are the prospects for avoiding these adverse outcomes? How might the global debt overhang be reduced in a way that could encourage growth? Some analysts posit that the political struggle on government spending is just posturing and that once matters become urgent and key elections are over sober minds will sit down and do the right thing. Others rely on highly debatable projections of growth, interest rates, unemployment and other key factors to put deficits on a glide path to sustainability. There is good reason to view these forecasts with doubt, even pessimism. The reason has to do with the dynamics of society itself. Just as currency wars and capital markets are examples of complex systems, so those systems form part of larger complex systems with which they interact. The structure and dynamics of these larger systems are the same—except the scale is greater and the potential for collapse greater still.

Complexity theorists Eric J. Chaisson and Joseph A. Tainter supply the tools required to understand why spending discipline will likely fail and why currency wars and a dollar collapse may follow. Chaisson, an astrophysicist, is a leading theorist of complexity in evolution. Tainter, an anthropologist, is also a leading theorist of complexity as it relates to the collapse of civilization. Their theories, taken together and applied to capital markets as affected by contemporary politics, should give us pause.

Chaisson considers all complex systems from the cosmic to the subatomic and zeroes in on life generally and humans in particular as being among the most complex systems ever discovered. In his book Cosmic Evolution, he considers the energy requirements associated with increasing complexity and, in particular, the “energy density” of a system, which relates energy, time, complexity and scale.

Chaisson posits that the universe is best understood as the constant flow of energy between radiation and matter. The flow dynamics create more energy than is needed in the conversion, providing “free energy” needed to support complexity. Chaisson’s contribution was to define complexity empirically as a ratio of free energy flow to density in a system. Stated simply, the more complex a system is, the more energy it needs to maintain its size and space. Chaisson’s theories are well supported, starting with the original laws of thermodynamics through more recent sophisticated local observations of increasing order and complexity in the universe.

It is well understood that the sun uses far more energy than a human brain. Yet the sun is vastly more massive than a brain. When these differences in mass are taken into account, it turns out that the brain uses 75,000 times as much energy as the sun, measured in Chaisson’s standard units. Chaisson has also identified one entity vastly more complex than the human brain: society itself in its civilized form. This is not surprising; after all, a society of brainy individuals should produce something more complex than the individuals themselves. This is wholly consistent with complexity theory, civilization being just an emergent property of individual agents with the whole greater than the sum of its parts. Chaisson’s key finding is that civilization, adjusted for density, uses 250,000 times the energy used by the sun and one million times the energy used by the Milky Way.

To see the implications of this for macroeconomics and capital markets, begin with the understanding that money is stored energy. The classic definition of money includes the expression “store of value,” but exactly what value is being stored? Typically value is the output of labor and capital, both of which are energy intensive. In the simplest case, a baker makes a loaf of bread using ingredients, equipment and her own labor, all of which use energy or are the product of other forms of energy. When the baker sells the loaf for money, the money represents the stored energy that went into making the bread. This energy can be unlocked when the baker purchases some goods or services, such as house painting, by paying the painter. The energy in the money is now released in the form of the time, effort, equipment and materials of the painter. Money works exactly like a battery. A battery takes a charge of energy, stores it for a period of time and rereleases the energy when needed. Money stores energy in the same way.

This translation of energy into money is needed to apply Chaisson’s work to the actual operation of markets and society. Chaisson deals at the highest macro level by estimating the total mass, density and energy flow of human society. At the level of individual economic interactions within society, it is necessary to have a unit to measure Chaisson’s free energy flows. Money is the most convenient and quantifiable unit for this purpose.

The anthropologist Joseph A. Tainter picks up this thread by proposing a related yet subtler input-output flow analysis that also utilizes complexity theory. An understanding of Tainter’s theory is also facilitated by the use of the money-as-energy model.

Tainter’s specialty is the collapse of civilizations. That’s been a favorite theme of historians and students since Herodotus documented the rise and fall of ancient Persia in the fifth century BC. In his most ambitious work, The Collapse of Complex Societies, Tainter analyzes the collapse of twenty-seven separate civilizations over a 4,500-year period, from the little-known Kachin civilization of highland Burma to the widely known cases of the Roman Empire and ancient Egypt. He considers an enormous range of possible factors explaining collapse, including resource depletion, natural disaster, invasions, economic distress, social dysfunction, religion and bureaucratic incompetence. His work is a tour de force of the history, supposed causes and processes of civilizational collapse.

Tainter stakes out some of the same ground as Chaisson and complexity theorists in general by demonstrating that civilizations are complex systems. He demonstrates that as the complexity of society increases, the inputs needed to maintain society increase exponentially—exactly what Chaisson would later quantify with regard to complexity in general. By inputs, Tainter refers not specifically to units of energy the way Chaisson does, but to a variety of potentially stored energy values, including labor, irrigation, crops and commodities, all of which can be converted into money and frequently are for transactional purposes. Tainter, however, takes the analysis a step further and shows that not only do inputs increase exponentially with the scale of civilization, but the outputs of civilizations and governments decline per unit of input when measured in terms of public goods and services provided.

Here is a phenomenon familiar to every first-semester microeconomics student—the law of diminishing returns. In effect, society asks its members to pay progressively more in taxes and they get progressively less in government services. The phenomenon of marginal returns produces an arc that rises nicely at first, then flattens out, and then declines. In this thesis, the familiar arc of marginal returns mirrors the arc of the rise, decline and fall of civilizations.

Tainter’s main point is that the relationship between people and their society in terms of benefits and burdens changes materially over time. Debates about whether government is “good” or “bad” or whether taxes are “high” or “low” are best resolved first by situating society on the return curve. In the beginning of a civilization, returns to investment in complexity, usually in the form of government, are typically extremely high. A relatively small investment of time and effort in an irrigation project can yield huge returns in terms of food output per farmer. Short periods of military service shared across the entire population can yield huge gains in peace and security. A relatively lean bureaucracy to organize irrigation, defense and other efforts of this type can be highly efficient as opposed to ad hoc supervision.

At the beginning of civilization, the research budget for the invention of fire was zero, while the benefits of fire were incalculable. Compare this to the development costs of the next generation of Boeing aircraft relative to the small improvements in air travel. This dynamic has enormous implications for the presumed benefits of increases in government spending beyond some low base.

Over time and with increasing complexity, returns on investment in society begin to level off and turn negative. Once the easy irrigation projects are completed, society begins progressively larger projects covering longer conduits with progressively smaller amounts of water produced. Bureaucracies that started out as efficient organizers turn into inefficient obstacles to improvement more concerned with their own perpetuation than with service to society. Elites who manage the institutions of society slowly become more concerned with their own share of a shrinking pie than with the welfare of society as a whole. The elite echelons of society go from leading to leeching. Elites behave like parasites on the host body of society and engage in what economists call “rent seeking,” or the accumulation of wealth through nonproductive means—postmodern finance being one example.

By 2011, evidence had accumulated to show that the United States was well down the return curve to the point where greater exertions by more people produced less for society while elites captured most of the growth in income and profits. Twenty-five hedge fund managers were reported to have made over $22 billion for themselves in 2010 while forty-four million Americans were on food stamps. CEO pay increased 27 percent in 2010 versus 2009 while over twenty million Americans either were unemployed or had dropped out of the labor force but wanted a job. Of Americans with jobs, more worked for the government than in construction, farming, fishing, forestry, manufacturing, mining and utilities combined.

One of the best measures of the rent seeking relationship between elites and citizens in a stagnant economy is the Gini coefficient, a measure of income inequality; a higher coefficient means greater income inequality. In 2006, shortly before the recent recession began, the coefficient for the United States reached an all-time high of 47, which contrasts sharply with the all- time low of 38.6, recorded in 1968 after two decades of stable gold-backed money. The Gini coefficient trended lower in 2007 but was near the all-time high again by 2009 and trending higher. The Gini coefficient for the United States is now approaching that of Mexico, which is a classic oligarchic society characterized by gross income inequality and concentration of wealth in elite hands.

Another measure of elite rent seeking is the ratio of amounts earned by the top 20 percent of Americans compared to amounts earned by those living below the poverty line. This ratio went from a low of 7.7 to 1 in 1968 to a high of 14.5 to 1 in 2010. These trends in both the Gini coefficient and the wealth-to-poverty income ratio in the United States are consistent with Tainter’s findings on civilizations nearing collapse. When society offers its masses negative returns on inputs, those masses opt out of society, which is ultimately destabilizing for masses and elites.

In this theory of diminishing returns, Tainter finds the explanatory variable for civilizational collapse. More traditional historians have pointed to factors such as earthquakes, droughts or barbarian invasions, but Tainter shows that civilizations that were finally brought down by barbarians had repelled barbarians many times before and civilizations that were destroyed by earthquakes had rebuilt from earthquakes many times before. What matters in the end is not the invasion or the earthquake, but the response. Societies that are not overtaxed or overburdened can respond vigorously to a crisis and rebuild after disaster, while those that are overtaxed and overburdened may simply give up. When the barbarians finally overran the Roman Empire, they did not encounter resistance from the farmers; instead they were met with open arms. The farmers had suffered for centuries from Roman policies of debased currency and heavy taxation with little in return, so to their minds the barbarians could not possibly be worse than Rome. In fact, because the barbarians were operating at a considerably less complex level than the Roman Empire, they were able to offer farmers basic protections at a very low cost.

Tainter makes one additional point that is particularly relevant to twenty- first-century society. There is a difference between civilizational collapse and the collapse of individual societies or nations within a civilization. When Rome fell, it was a civilizational collapse because there was no independent society to take its place. Conversely, European civilization did not collapse again after the sixth-century AD, because for every state that collapsed there was another state ready to fill the void. The decline of Spain or Venice was met by the rise of England or the Netherlands. From the perspective of complexity theory, today’s highly integrated, networked and globalized world more closely resembles the codependent states of the Roman Empire than the autonomous states of medieval and modern Europe. In Tainter’s view, “Collapse, if and when it comes again, will this time be global. No longer can any individual nation collapse. World civilization will disintegrate as a whole.”

In sum, Chaisson shows how highly complex systems such as civilizations require exponentially greater energy inputs to grow, while Tainter shows how those civilizations come to produce negative outputs in exchange for the inputs and eventually collapse. Money serves as an input-output measure applicable to a Chaisson model because it is a form of stored energy. Capital and currency markets are powerful complex systems nested within the larger Tainter model of civilization. As society becomes more complex, it requires exponentially greater amounts of money for support. At some point productivity and taxation can no longer sustain society, and elites attempt to cheat the input process with credit, leverage, debasement and other forms of pseudomoney that facilitate rent seeking over production. These methods work for a brief period before the illusion of debt-fueled pseudogrowth is overtaken by the reality of lost wealth amid growing income inequality.

At that point society has three choices: simplification, conquest or collapse. Simplification is a voluntary effort to descale society and return the input-output ratio to a more sustainable and productive level. An example of contemporary systemic simplification would be to devolve political power and economic resources from Washington, D.C., to the fifty states under a reinvigorated federal system. Conquest is the effort to take resources from neighbors by force in order to provide new inputs. Currency wars are just an attempt at conquest without violence. Collapse is a sudden, involuntary and chaotic form of simplification.

Is Washington the New Rome? Have Washington and other sovereigns gone so far down the road of higher taxes, more regulation, more bureaucracy and self-interested behavior that social inputs produce negative returns? Are certain business, financial and institutional elites so linked to government that they are aligned in the receipt of outsized tribute for negative social utility? Are so-called markets now so distorted by manipulation, intervention and bailouts that they no longer offer reliable price signals for the allocation of resources? Are the parties most responsible for distorting the price signals also those receiving the misallocated resources? When the barbarians arrive next time, in whatever form, what is the payoff for resistance by average citizens compared to allowing the collapse to proceed and letting the elites fend for themselves?

History and complexity theory suggest that these questions are not ideological. Instead they are analytic questions whose relevance is borne out by the experience of scores of civilizations over five millennia and the study of ten billion years of increasing complexity in nature. Science and history have provided a complete framework using energy, money and complexity to understand the risks of a dollar collapse in the midst of a currency war.

What is most important is that the systems of immediate concern— currencies, capital markets and derivatives—are social inventions and therefore can be changed by society. The worst-case dynamics are daunting, but they are not inevitable. It is not too late to step back from the brink of collapse and restore some margin of safety in the global dollar-based monetary system. Unfortunately, the deck is stacked against commonsense solutions by the elites who control the system and feed at the trough of complexity. Diminishing marginal returns are bad for society, but they feel great for those on the receiving end of the inputs—at least until the inputs run dry. Today, the financial resources being extracted from society and directed toward elites take the form of taxes, bailout costs, mortgage frauds, usurious consumer rates and fees, deceptive derivatives and bonuses. As citizens are crushed under the weight of this rent extraction, collapse grows more likely. Finance must be returned to its proper role as the facilitator of commerce rather than a grotesque end in itself. Complexity theory points the way to safety through simplified and smaller-sized institutions. Incredibly, Treasury Secretary Geithner and the White House are actively facilitating a larger- scale and more concentrated banking industry, including a protoglobal central bank housed at the IMF. Any success in this endeavor will simply hasten the dollar’s dénouement.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46