Marilyn Monroe

Marilyn Monroe defined the terms “movie star” and “sex symbol” during her lifetime, and she continues to define them now, nearly five decades after her controversial death. She was shamelessly sensual but fragile, intelligent but helpless, ambitious but difficult, an icon of perfection but deeply flawed.

On June 1, 1926, in Los Angeles, California, Gladys Monroe Baker gave birth to a daughter she named Norma Jeane. Norma Jeane’s paternity has never been authenticated, although Gladys’s estranged husband, Edward Mortenson, is listed on the birth certificate. Whoever fathered Norma Jeane Baker, though, was definitely nowhere to be found, nor was Gladys on a regular basis. Mentally unstable and institutionalized from time to time, Gladys handed over most of the care of her daughter to a succession of orphanages, guardians, and foster homes, in some of which she was reportedly abused.

In June 1942, when she was sixteen, Norma Jeane married James Dougherty, a marriage arranged to keep her out of yet another foster home. Dougherty enlisted in the Merchant Marines in 1943 and during World War II left his young wife in the care of his mother. Norma Jeane was hired by a munitions factory, where she was photographed for an article in Yank

magazine. As a result of that photograph, she was signed by the Blue Book Modeling Agency and, with its encouragement, transformed herself from a brunette to a blonde and became a successful model who began to dream of an acting career. Dougherty demanded, when he returned home, that she choose between their marriage and her career. She chose her career and divorced James Dougherty in 1946.

Norma Jeane quickly captured the attention of Ben Lyon, a Twentieth Century Fox executive, who signed her to a six-month contract and changed her name to Marilyn Monroe. After a couple of nonstellar film appearances in 1947, Marilyn was released from her obligations to Fox and returned to modeling until 1948, when she signed a six-month contract with Columbia Pictures.

It was her appearance in a Marx Brothers film called Love Happy in 1949 that attracted a successful agent named Johnny Hyde, who promptly signed her and was instrumental in landing critically acclaimed roles for her in John Huston’s The Asphalt Jungle

and Joseph Mankiewicz’s All About Eve. Hyde is also credited with negotiating Marilyn’s seven-year contract at Twentieth Century Fox in 1950.

Her film career was well on its way by the end of 1952 despite the stage fright that had begun to plague her, causing her to hide in her dressing room for hours while the rest of the cast and crew waited impatiently for her. She graced the cover of the first issue of Playboy in 1953, the same year in which she was suspended from her Fox contract for failing to appear for work and in which she met baseball superstar Joe DiMaggio, whom she married on January 14, 1954, a marriage that lasted less than a year.

Displeased with the quality of roles being offered to her by Fox and with the relatively small salary, Marilyn broke away from the studio and moved to New York, where she studied acting at the famed Lee Strasberg Actors Studio and began dating playwright Arthur Miller, whom she married on June 29, 1956. Her severe stage fright continued to plague her throughout her acting classes, but she was also recognized as a genuinely gifted standout. In the meantime, her film The Seven Year Itch was released to enormous success, and she re-signed with Twentieth Century Fox with a much more lucrative nonexclusive contract.

Under her new contract Marilyn starred in Bus Stop and The Prince and the Showgirl with critical acclaim and relatively few problems. She took a year off to focus on her marriage to Arthur Miller, but she sadly suffered a miscarriage in August

1957. She returned to Hollywood in 1958 to shoot Billy Wilder’s Some Like It Hot, costarring Jack Lemmon and Tony Curtis, during which her compulsive tardiness, hostile refusal to take direction from Wilder, and general obstructive behavior contributed to her growing reputation for being difficult to work with. But the film was a huge box-office success, received five Academy Award nominations, and earned Marilyn the Golden Globe Best Actress Award.

By the late 1950s Marilyn’s health was in a conspicuous decline, due largely to a growing dependence on prescription medication, particularly sleeping pills to battle her chronic insomnia, and the strains on her marriage were becoming more and more apparent.

Arthur Miller had written a screenplay called The Misfits, which began filming in July 1960 with Marilyn, Clark Gable, and Montgomery Clift, directed by John Huston. It was to become Marilyn Monroe’s last completed film. She was often too ill and too anxious to perform, her fragile health further compromised by a steady stream of prescription medications and alcohol. A month after filming began she was hospitalized for ten days with an undisclosed illness, and when she returned to the set her open hostility toward her husband was a recurring obstacle. Clark Gable became ill while shooting The Misfits as well, and less than ten days after filming was completed, Marilyn Monroe and Arthur Miller officially separated and Clark Gable was dead from a heart attack.

Marilyn’s addictions to alcohol and prescription drugs escalated following the lackluster box-office performance of The Misfits, and in February 1961, once her divorce from Arthur Miller was finalized, she checked into a psychiatric clinic. For the remainder of 1961 she battled a series of mental and physical health challenges, with her former husband and still loyal friend Joe DiMaggio by her side.

In 1962 she started filming Something’s Got to Give, but her repeated failure to report to work forced Twentieth Century Fox to fire her and file a lawsuit against her. On May 19, 1962, she gave an unforgettably breathy, voluptuous, and somewhat slurred performance of “Happy Birthday” at the birthday celebration for President John Kennedy, with whom she was later reported to have had an affair. She launched into a busy series of interviews, photo shoots, and meetings about future projects. She and Fox resolved their dispute, and they renewed her contract. And Something’s Got to Give was scheduled to resume filming in the early fall of 1962.

But at 4:25 a.m. on the morning of August 5, 1962, Marilyn’s psychiatrist, Dr. Ralph Greenson, placed an emergency call to report that she’d been found dead in her small Brentwood, California, house. She was just thirty-six years old. Following an autopsy, the cause of death was listed as “acute barbiturate poisoning—probable suicide.” Even now, nearly fifty years later, the circumstances surrounding her death continue to create any number of theories and allegations, including homicide. Marilyn Monroe was laid to rest on August 8, 1962, in the Corridor of Memories at Westwood Memorial Park, leaving behind a legacy of thirty films and an iconic standard of beauty and glamour at their most vulnerable that will never be duplicated.

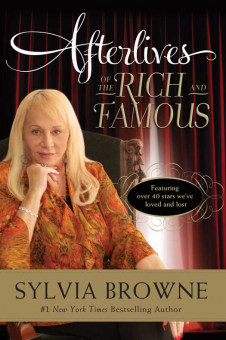

From Sylvia

Several years after Marilyn’s death I was asked by a nationally syndicated television show to visit her house with a film crew to see if she would communicate with me. A condition of filming on their part was that I wouldn’t be allowed inside the house or even that close to it—just inside the gate was as far as we could go. A condition on my part was, “No promises.” There are no spirits or ghosts who can be counted on to come when I call them, and I hadn’t even established yet whether Marilyn had made it to the Other Side or if she was still earthbound. For all I knew we could end up with a lot of footage of me standing in front of a house staring mindlessly into the camera without a peep out of Marilyn.

I admit it, I’d done no research on her life before I arrived, so I didn’t think much about being introduced to a lovely older gentleman named James Dougherty until I was told he was her first husband. He was quick to clarify that he’d never been married to Marilyn Monroe; he was married to the young (pre-Marilyn) Norma Jeane Baker. He spoke of her with deep affection, and her death had touched him deeply.

As soon as we’d arrived as close to the house as we were allowed to get, a brief Latin phrase came to me. I pronounced it as best I could, and when I saw him staring at me, I explained, “It’s in the tiles above the entryway. It means something like ‘Everyone is welcome here.’”

He asked how I knew about that, since I’d never been to the house before, and I told him. “Marilyn’s telling me.”

It was a nice surprise. She was definitely on the Other Side, she definitely had a lot to say, and she was ready to say it to me without preferring to talk through Francine. I can’t judge or comment on its accuracy. I’ll just report what she passed along and leave the rest to you.

She was adamant about the fact that she did not commit suicide. She described being alone in her bedroom that night, taking too many pills and making some blurry phone calls. But she had a clear memory of a man coming in and sticking a needle of what she believed to be Nembutol into her heart.

She never stopped loving Joe DiMaggio, and one of the sources of depression that plagued her in her later years was the fear that, because she confided so much in him about things she undoubtedly wasn’t supposed to know, which she’d written in a red journal or diary, loving her might have brought him more pain and potential danger than joy. She visited him often from the Other Side, particularly when he slept, and she was already determined to be the first to greet him when he came Home.

Then she was gone. Even in that brief encounter, I was pleasantly surprised at how much I liked her and the depth of her sincerity.

From Francine

Marilyn was indeed the first to welcome Joe DiMaggio Home. They lead very quiet separate lives here, but they also spend a lot of time together walking on the beach. Marilyn is a voracious reader and can often be found studying the great literary classics in the Hall of Records.

Like everyone else on the Other Side, she looks back on her most recent lifetime with increasing clarity. She knows she was bipolar. She knows that she was at her most comfortable when she was acting—pretending to be someone else. She knows that if she’d lived a long life, she would never have been the icon she’s become. She just wants those who try to emulate her not to fall into the same trap she did, the excess that comes with fame. People stop saying no to you. You stop saying no to yourself.

And before long you’ve forgotten what a loving word “no” can be.

Pages: 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54